Pat Shaughnessy’s “Using a Ruby Class to Write Functional Code” gives an example of bringing functional programming principles into object-oriented design. I like it.

It Pat’s example, he turns a group of pure functions into a class whose state is immutable-ish (they technically could be changed, but they aren’t) & whose methods are pure-ish (they read from internal state, too). He says:

You’ve broken the rules and rewritten your pure, functional program in a more idiomatic, Ruby manner. However, you haven’t lost the spirit of functional programming. Your code is just as easy to understand, maintain and test.

One commenter goes further:

I think you do not break the rules of FP by relying on

@lineand@values.@lineis just partially applying a parameter to the “functions” of Line and currification is a usual techique in FP.@valuesis memoizing the result of a function which also comes from FP.

There were a few ideas that jumped out at me.

“No Side-effects” = Clarity at the Call Site

Functions that don’t modify their arguments are often easier to use. Their usage reveals intent.

Which do you prefer:

def exclaim_1(statement)

# modify the argument

statement << "!!!"

return nil

end

wow = "Wow"

exclaim_1(wow) # => nil

wow # => "Wow!!!"

or:

def exclaim_2(statement)

# make a new string

return statement + "!!!"

end

wow = "Wow"

such_wow = exclaim_2(wow) # => "Wow!!!"

wow # => "Wow"

such_wow # => "Wow!!!"

In the first case, if you didn’t have the output in front of you, you wouldn’t know what exclaim_1 did. You’d have to find the file and read the method body to know its purpose.

In the second case, it’s obvious at the call site that the function returns a new, significant value. (Otherwise, why would the developer have captured in a new variable?)

Think of self as an Argument

You can extend the benefit of call site clarity to an object’s internal state, too.

The commenter mentions that “@line is like a parameter” to the class’s methods. Although it isn’t part of the method signature, it has some parameter-like properties. It is:

- A value which affects the output

- Unchanged by the function

What if you always treated self like that? I mean, you didn’t modify it inside method bodies, you treated it as read-only (as often as possible).

Python really invites you to think of self as a parameter of the function. It’s actually part of the method signature:

class Something():

def some_method(self, arg_1, arg2):

self # => the instance

return "whatever"

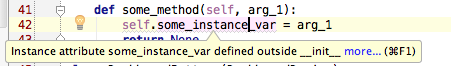

In fact, PyCharm will even complain if you modify self during a method:

(In reality, self is an argument in any language runtime that I ever heard of … we just tend not to think of it that way!)

What Gives?

I spend most of my time maintaining software and FP pays off big time in that regard:

- Tests are more reliable for pure functions: if the function yields the correct output with those inputs today, it will always yield the correct output with those inputs.

- Pure functions are easy to understand: the only factors are the inputs and there’s no muddling from outside universe. Knowledge of the function body is sufficent to understand the function.

- Pure functions must be decoupled. The only touch the world via inputs and outputs so they can’t depend on anything else.